Between Earth and Body: Standing at the Shore with Smita Sen

How Smita Sen’s Sculptures and Performances Speak to the Healing Power of Art.

Smita Sen’s work is magnetic—a quiet pull that refuses to let go. Her pieces invite not just observation, but immersion, creating a space where you are less an audience and more a participant in the emotional and physical exchange unfolding before you. Embodied, the artist’s latest show, at MOCA North Miami promises to continue this exploration, guiding viewers through a flow of grief, memory, and the body—shifting from the personal to the collective in a seamless, almost spiritual progression. With works like Grief Tectonics, and previous works such as Light Body Being, Sen transforms the landscape of human experience, using her own body as a vessel for material manifestations of her renewed consciousness of self.

Through 3D-printed sculptures, movement, and a deep engagement with sound, Sen probes the complex interplay between personal loss and larger forces—whether geological, cultural, or social. At the heart of her practice is the legacy of her father, a geologist whose work reshaped her understanding of memory, space, and time. As she reflects on these influences and her ongoing process of discovery, Sen also highlights the fractured healthcare systems that influence how we experience healing, offering a profound meditation on resilience, transformation, and the power of shared vulnerability across communities grappling with different spectrums of tragedy.

Olisa Tasie-Amadi: I want to start by speaking about your work, Light Body Being. It was one of the first pieces I saw on your website, and I think it offers a great introduction to your practice. I’m curious to know, looking back on that piece, how you feel it reflects your emotional and spiritual articulations, especially in relation to where your work is now. Has your understanding of that piece evolved over time?

Smita Sen: Wow, thank you for starting with Light Body Being. It’s such a special piece for me, and I’m glad you brought it up. At the time, I was transitioning between keeping my dance and visual art practices separate. Light Body Being marked the beginning of integrating my body and movement more holistically into my visual work. I remember being in the studio, working with collages, and sitting in winter light when I started recording myself. The light had this surreal effect, almost making me disappear, and I captured that without any edits — it was just as it appeared in the moment.

The piece was very much about merging my embodied practice, my meditation, and my movement into something visual. I’ve been meditating since I was around 11, not because of any spiritual background but because I was a hyperactive child, and my mom thought it might help me channel my energy. Meditation gave me a way to connect to something larger than myself, beyond religious dogma. That idea of surrendering to something greater, and the lightness of Light Body Being, was my first attempt to visually express that connection.

O: I love the way you’ve described your work as a kind of devotional act. There’s something so powerful about the way light interacts with your body in that piece — almost as though it’s part of you rather than something you’re subject to. This makes me think about the relationship between healing and spirituality in your work. You mentioned your meditation practice and the notion of a larger connection, which seems to permeate your art. Do you see healing and spirituality as directly linked in your practice? Or as individual entities existing as a pair?

S: Yes, absolutely. The connection between healing and spirituality is deeply intertwined for me, especially when it comes to the medical and spiritual dimensions of illness. I’ve thought a lot about how illness transforms the body — physically and metaphysically — and the way the body responds to both extreme illness and caregiving. There’s something deeply humbling about the way illness forces you to confront your fragility. I’ve seen it firsthand, particularly with my father’s illness, and experienced it in my own life as well.

Doctors, if they’re good, are incredibly gentle, but I’ve also witnessed the ego-driven side of medicine, where the doctor’s authority can strip away the patient’s autonomy. That feeling of being trapped in a system — being unable to leave the hospital, for example — is overwhelming. I once ran away from a hospital during an asthma attack because I didn’t like the energy there. It’s funny, looking back, but in that moment, I just had this overwhelming urge to escape. The physicality of that — the adrenaline, the fight-or-flight response — is something I think a lot about in my work. For my dad, however, it was more about a deep need to return to safety, and to be with his family.

O: That’s interesting how you describe that physical impulse and the way it contrasts with your father’s desire for peace. There’s a sense of space in your narrative — the hospital as a site of chaos, and your father’s longing for safety. Can you talk more about when you began to understand your body storing these emotions as geological planes?

S: My father was a geologist, which is where my exploration of geological space comes from. I think about how the body — and emotions — can be understood through these vast scales of time and space. In a hospital, there’s this very compressed sense of time, with machines constantly ticking away, beeping, or the crying and sounds of distress filling the space. It’s overwhelming. When I think about geological time, though, it’s expansive, measured not in minutes but in millennia. In the face of illness, I find comfort in the idea that the body is part of something far greater than itself — a vast continuum. There’s something deeply grounding in that. The fragility of our bodies, how quickly we can feel finite, is juxtaposed with the immense, enduring nature of the earth.

O: Do you see your performances as a way of revisiting past experiences of loss and grief, transforming them as you do? Considering as well the role of memory in this, particularly in how we perceive and process emotions in the body?”

S: I think of time not as linear but as cyclical, and my work, particularly Rituals of Sacred Surrender, reflects that. Trina Basu and I created that piece in 2021, two years after my father’s passing, and every time I return to it, I can feel how much I’ve changed. The movements we created are always adapted and reshaped depending on where I am in my life at that moment. It’s like the work lives with me, shifting and evolving as I do. I’m also working on a piece called Grief Tectonics, which is about the transformation of the earth — how the ocean can turn into a desert, and the desert into the ocean again. It speaks to how experiences transform, flip inside out, and come back to us in new forms. So much of my work grapples with this idea of cycles — of returning to the same questions and ideas but viewing them from a different perspective each time.

O: How does the shifting fragility of memory — both in terms of emotional and physical space — influence your performative work, particularly in relation to sonic memory, and how does the ritualistic quality of your performances connect to this almost mutating process?

S: When I think about sound and sonic memory, I come back to my opera training. It’s an unusual background for me, but I was always more drawn to strange, primal sounds rather than traditional opera repertoire. These days, when I warm up my voice, I don’t focus on hitting a high note or reaching a particular pitch. Instead, I focus on breathing. Singing, for me, is just breathing. When I think of it this way, it opens up something much deeper and more interesting within my body.

The way we’re trained as singers is fascinating because the voice isn’t just in your throat; it’s connected all the way down to your pelvis. It’s a full-body experience. And when you’re singing, you’re breathing — and in that process, you’re summoning memories within your body. You start observing yourself, shifting your focus to where you feel tension, and noticing things you didn’t realize were there. Each performance teaches me something new about myself. If it’s a good performance, I’ve learned something about myself and observed my own emotional state in a way that’s honest and true.

O: I think, especially in terms of how you describe the act of singing, it’s a practice of connecting to your body and your memories. In terms of the sounds that have shaped you, what kinds of sounds—whether it’s music, nature, or something else—do you think have led you to a deeper understanding of yourself?

S: When I first started training, I was focused on music in a very technical way—listening for virtuosity, looking for what sounds "good." But over time, I shifted my focus to the world around me—the sound of trains, honking cars, people breathing, nature’s sounds. I became more attuned to the sounds closest to me, like my heartbeat, which is actually the sound we hear first in meditation. From there, you expand outward, listening to your breathing, the sounds your body makes as it moves, the rustling of your clothes.

That kind of listening makes the world sound more vivid and rich, and it opens up a new landscape to build from when creating. When I work with Trina—who’s an incredible violinist—we spend a lot of time listening. She’s pushed me to really focus on listening intently, which has made me a better artist.

O: On your connection with Trina, what was it like to develop that kind of relationship both personally and professionally?

S: Trina is like family to me. Her parents are friends with mine, and she’s from Miami, so we’ve known each other for a long time. She’s kind of like an older cousin to me. We reconnected when I was in college and decided to pursue the arts more seriously. It’s rare to have someone in your family or close circle who is not only an artist but someone who’s making a living off it.

Trina’s a world-class violinist and an electronic artist, and I think she really believed in me and my potential. After my dad passed away, she became more involved in my life, both personally and professionally. She’s someone who has both seen my family dynamics and understood the personal side of things. Our connection is deep, and it’s been an incredible balance of personal and professional respect. I feel incredibly lucky to have her as a collaborator.

O: I want to take it back to the idea of healthcare, especially in terms of how you’ve responded to the commodification of healthcare and the meditation spaces in your work. How do you grapple with the disconnect between the idea of a sanctuary space vs. the reality of what the healthcare system has become, especially in Western society?

S: When we were leaving the hospital after my father’s passing, the experience was incredibly jarring. Hospitals, especially the morgue, are run under such a different structure once someone has passed away. The doctors disappear, and you’re left in this almost bureaucratic limbo. If they don’t label the body properly, it can get lost in the system. There was a lot of anger, a lot of betrayal.

We had always hoped that science and medicine were there to improve humanity, but our encounter with the medical system revealed just how flawed it is. That anger became fuel for creating healing spaces. It was a way to take that resentment and turn it into something positive. The sanctum we created allowed people to share their personal stories and frustrations with the healthcare system. It became a space for confronting that anger while also honoring the emotional realities of the people in the room.

O: You also raise an important point about how, when people confront the flaws in a system, they often feel stuck because the alternatives may not be much better. For example, in Nigeria, where I’m from, the healthcare system feels even worse than in the U.S., so for many, the American system might seem like the best available option. But even then, it feels like an illusion of perfection. How do you navigate this? How do you help people see the cracks in this illusion and potentially shift their perspective through your work?

S: One experience in the sanctum really clarified things for me. We had a sound healer who shared her story. She had been in a serious accident as a child, and in order to receive the insurance payout, doctors had to declare she would never recover. It was the only way to garner that help, but it also affected the way she understood/contended with her trauma as well. This lie, told to a child, was part of a system that prioritized profit over care.

It made me realize that anger is the appropriate response in situations like that — it grounds the truth of what’s happening. The ugliness of a healthcare system driven by financial motives dehumanizes people. But anger is also powerful. There’s a Bengali saying, Raagi Lokki, meaning "anger is divine," connected to Lakshmi, the goddess of prosperity. In this sense, anger is a reminder of what’s wrong and a call for change. I think the sanctum provided a space to hold both the anger and the healing. It wasn’t about suppressing one in favor of the other, but acknowledging both as part of the process—seeing the flaws in the system while working to create something better.

O: Are there new sonic landscapes you’re exploring? What role do you see for the audience in engaging with your work in regards to its meaning-making for both the physical works but also the intent behind the space?

S: Yes, there’s a new dance film composed by Roshni Samlal, a brilliant tabla player and electronic artist. We worked together to create a sonic landscape that represents two types of grief—one that’s angry and resistant, and the other that’s softer, dissolving. In the piece, myself and another dancer are circling each other, navigating this desert landscape. These two energies are pushing against each other, and the soundscape reflects that tension.

O: I just have to say, I love the sculptures you created—they were incredible!

S: You’re so kind, thank you!

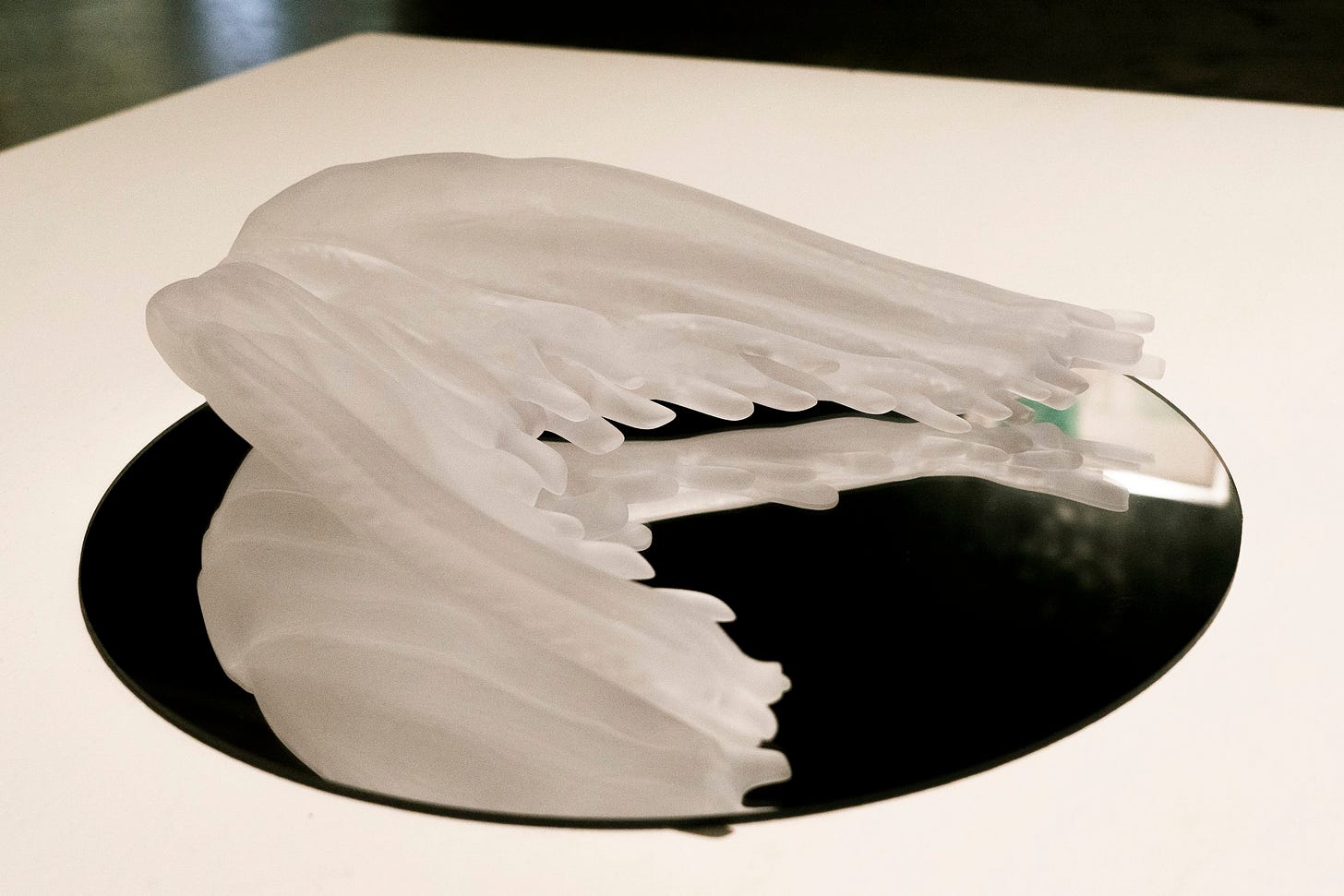

O: I think I remember seeing Breathing Sideways for the first time, and thought it telegraphed this image of an angel wing. Is that what it was supposed to represent?

S: Ah, that’s funny you say that, because a lot of people think it’s an angel wing. It’s actually about this hip pain I had on my left side—it’s like this lateral pain that stayed with me for a long time after my dad passed. It was really persistent, and I kept connecting it to the grief I felt at that time. The pain just wouldn’t go away, and I spent a lot of time working through it. So when I visualized it, I wanted the form to have that sinewy, fibrous quality—something that felt like muscle or tendon.

But when I close my eyes and think about it, that’s really what it looks like to me. I mean, it sort of resembles an angel wing, which is kind of hilarious, considering it’s about pain, not something spiritual. But I guess that’s the beauty of art—it can transform something painful into something beautiful and meaningful in its own way.

O: I think what’s really powerful is how you connect that pain to something much larger. The way you’ve expressed it, not just as an individual experience, but as something collective—like ghost pains in the body, right? That idea of how trauma is carried not just by an individual but by the body and by the collective. How do you see your work articulating that intersection of the personal and the communal, especially with the organic and synthetic elements in your sculptures?

S: What’s interesting for me is that when I create these pieces, I’m pulling out parts of myself—but they’re also universally shared experiences. I was talking with someone who said, I feel like you drew exactly what I’ve been experiencing. And that connection, that ability to articulate something so personal yet so relatable, is really special. It’s like using anatomy—getting physically close to realism in a way that speaks to the body’s own memory and experience. It’s both deeply felt and deeply embodied. And then, when others see themselves in that pain, they understand it as something part of them. It becomes this transformative moment where we’re reminded of how interconnected we all are—how deeply connected we are in our suffering and healing.

And caregiving, too—so much of caregiving involves the caregiver feeling and mirroring the suffering of the one being cared for. That shared pain, that interdependence, is critical. At the personal level, yes, but also on a societal level. Groups experience pain together, and I think art can express that collective, shared grief. That’s a big part of what I’m trying to convey with my work.

O: I love that you bring the caregiver into the conversation as well. It’s a great point about how art can capture not just the individual but also the labor, the nourishment, and the fragility of both the giver and the receiver. When you’re creating work that touches on these complex dynamics, do you go into the process with a set plan, or do you approach it as something more fluid—where the interactions and energies of the people engaging with the work might shape the experience in unexpected ways?

S: I love seeing how people respond to the work. It’s always fascinating to see what people notice, what they connect to. Sometimes they see things that I didn’t even consider or didn’t expect. But in terms of creating, I’m pretty open. I don’t have a rigid framework going into it. I think art is meant to evolve and change depending on the people who interact with it, and I like to see how that happens. Every story is different, and every person who enters the space can shift the mood or the energy of the work. That fluidity is important to me. It’s about creating a space for people to experience something real, and sometimes that requires flexibility.

O: As the show draws closer, do you feel any anxiousness or nerves about how people might respond, especially with the personal elements you’ve woven into it?

S: It’s always a little nerve-wracking, especially when I see people engage with the work in such a deeply personal way. Some visitors come up to me afterward and share that they’ve just lost someone and how the work really spoke to them. It’s always so moving. Sometimes, I even tear up in the gallery because, in those moments, I realize that this is exactly why I made the work—to connect with others in this very human way.

That’s when I know that the work has served its purpose, and it gives me so much meaning. It’s not about fame or recognition; it’s about those genuine, heartfelt connections with people. That’s what art is really about. It’s those moments of real human connection that remind me why I do what I do.

O: That’s so powerful. I love how you described it—it’s almost as though, in sharing that pain and experience, the art becomes its own form of caregiving. And on a personal level, how do you balance the drive to create with the need to take care of yourself outside of your work?

S: I think it’s a constant balance. From the very beginning, I gave myself permission to step away from art if I needed to—to live a “regular” life, take care of my family, and have a career outside of being an artist. But there’s this deep drive within me, too. Creating art is like exercising demons. It’s an intense, almost compulsive need to express something. I’ve made peace with the fact that if I’m going to make this a part of my life—this career—I want it to have real meaning. It has to matter to me and to others.

The moment the work stops feeling meaningful is when I’ll step away. But as long as it resonates with others, and as long as I feel like I have something to say, I’ll keep making art. Because at the end of the day, it’s about connecting with people in an authentic way. That’s what keeps me going.

Smita Sen’s Embodied is on view at the MOCA North Miami from November 6, 2024 - April 6, 2025